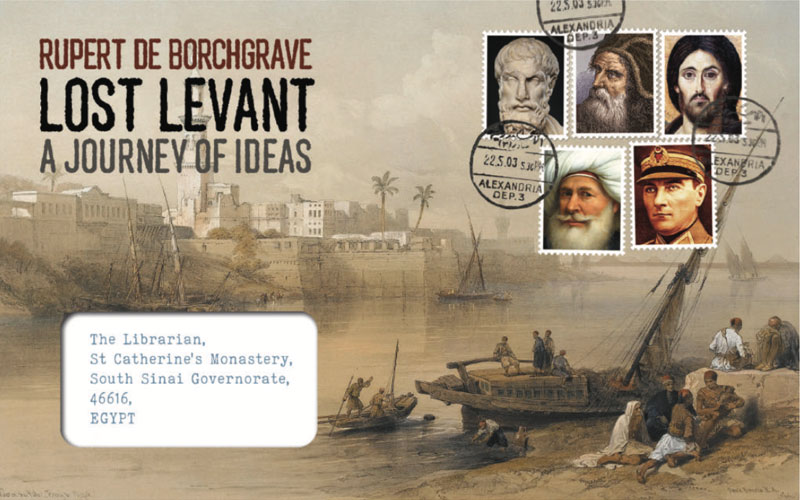

In the 18th century, young gentlemen went off to see what was left of the Classical world. In 2003, Rupert de Borchgrave went off to see what is left of ‘the Orient’

NEW FROM ENVELOPEBOOKS

Farewell, Sweetpea,’ I say, kissing my tearful girlfriend goodbye as she leaves for work. Pyrrha is going to hold the fort, tiny as it is: water the plants, collect the post and be at the end of the telephone in case of disaster. After attending to some last-minute necessities, and deciding on the right amount of cash for emergencies (I follow a friend’s sage advice and take very little), I post books to Father Justin in Sinai and James Mackay in Hatay to cover that other more serious hazard, namely running out of reading material.

At eleven o’clock I turn the key in the door of my Pimlico flat and walk over Vauxhall Bridge. I am carrying a green rucksack, a yoga mat and, slung over my shoulder, a large stripy canvas bag full of books. Despite trying to keep to eight kilograms—Roman soldiers on the march never carried more than ten per cent of their bodyweight—my bags are too heavy. But the first steps of a long solitary journey are bound to be tremulous and there is no time now to repack. Setting off for Mount Ararat via Sicily and Tunis, I take the train to Waterloo. By the Eurostar terminal I buy The Independent and browse the articles discussing weapons inspectors, international law and the British government’s support for the planned American invasion of Iraq.

The Eurostar is wonderful. Only the briefest of torments and you cross to

the continent at speed. Soon the train is ascending from the depths of the bedrock and you know your chances are good. No Bernoulli Effect. No circling in a spacecraft above crowded cities. No faith in the rivets of an unknown welder. I think of the family who escaped boarding doomed flight TWA 800 because there was no space in the hold for the coffins of their recently departed relatives: saved from death by the dead.

Arriving in Paris on a spring afternoon, I walk down the hill to Opéra wondering how I am going to carry this deadweight all the way to Ararat. I take the metro to Pereire and find a bar on the square. As I watch the world go by, the Cabinet in London is deciding that owing to France’s statement that ‘there are no grounds for waging war to … disarm Iraq’ the diplomatic process is over and Parliament will be asked to endorse military action. As I observe the busy streets in the evening light, I am unsure whether to feel liberated or fearful about embarking on a six-month pilgrimage. But there is nothing like the pleasure of simple French indulgence: croque and bière blonde. As the alcohol takes effect, it occurs to me how strange it seems: all these people rushing pensively home, not knowing quite what day it is, or even possibly which year they are in, only to set off again in the opposite direction in the morning. I sit on the brink of total freedom with no greater obligation hanging over me than to find a place to sleep and decide where to go next.

I buy flowers for my hosts, Giles and Anna, student friends and now career diplomats. After cooing over their newly born son, we launch into a furious discussion about the legitimacy of the imminent invasion of Iraq. Giles is loyal to the government he serves and advocates for the official British position. Having participated in street protests against the war, which culminated in the million-strong ‘Stop the War Coalition’ demonstration in London on 15 February, my views are sharply opposed to his. Giles says that Iraq is believed to have stockpiles of anthrax and refers to the arguments about democracies not going to war against each other. I argue that an illegal war is state-sanctioned murder: there is no firm evidence that Iraq possesses weapons of mass destruction, nor that the Iraqi government has links to Islamic terror groups. Can a diplomatic solution not be found to remove Saddam through some sort of plea bargain without killing tens of thousands of innocent Iraqis? Is this invasion not going to destabilise the country and lead to many more years of conflict?

ORIGINS OF A JOURNEY

What is the purpose of this ‘Grand Tour’? To escape the domestic project on a shoestring? To cling to youth and slow the years as they cascade over each other at an ever-accelerating rate? To satisfy wanderlust and the restless urge to see the world? Certainly all of these. Weary of putting numbers in boxes in drab provincial towns, baulking at the prospect of shackled domesticity and never having had the chance to escape the taut bonds of our damp, cramped northern isle, I decided to slip the noose. It was my thirty-second year. ‘You want to find yourself?’ a colleague asked. He pulled me in front of a mirror and jibbed: ‘There you are! Now get back to work!’ But it was inspiration and enchantment I sought, not just escape. The quest was more for Calypso than Penelope; the spirit of it more Gilgamesh than Odysseus.

Friends sent me farewell greetings. ‘There is something deep and certainly historic about our need to wander. By travelling, we establish contact with parts of ourselves that get lost in the passage of ordinary stationary life,’ wrote one. ‘How envious I am of you, to make a journey across the ‘Levant’. Ah that term conjures up a long past era, when European gentlemen explored the ‘mysterious Orient’. I hope you record your impressions, for gone are them days!’ said another. Surely, I thought, they always were?

Taking local public transport, I set off to explore the eastern Mediterranean and its hinterland, from Sicily to Cyrenaica, from Siwa to Syria, from Aleppo to Ararat. There may be nothing mysterious about ‘the Orient’. But travelling allows one to see life and society from a different vantage point. Where better than the lands of the source of our civilisation to imagine the distant past and gain perspective on the follies of the moderns? Where better than the Levant to discover secret places whose pre-modern spirit is preserved? I planned of course to report my impressions, like Darwin collecting specimens on the Beagle.

Woven into the diary of a physical voyage, recording places visited, people encountered and friendships made, this book relates a journey of ideas through a series of essays. About what? Love and money, since these are the most enduring of human motivations. Then there is philosophy and history too—between the dialogues, the landscapes and the ruins. This book is a book of books that represents a quest for universal humanism: Western cultural history is reinterpreted as a philosophy of liberation that finds its expression in a theory of political economy called ‘Epicurean economics’. But it is not an easy task to integrate a total worldview. For in all the currents of human thought, there are no complete systems that make sense of all experience. That is why people are fond of slogans and pre-packaged ideologies, not to mention all the distractions the modern world provides in ‘getting on with life’: it stops them from having to think.

TUESDAY 18 MARCH | AVIGNON

During the night, the American Presi

END OF SAMPLE

LOST LEVANT

RUPERT DE BORCHGRAVE

EnvelopeBooks, 1 May 2025 Softback, 496 pages 9781915023513

Advance copies and book club orders from envelopebooks.co.uk