The trial was for sorcery, the accused was a woman. Her name was Samanta and she was a peasant from a backwater village called Bussana. I assisted in her trial, though whether by chance or by the hand of God, I cannot say.

I had been staying at the newly-constructed Abbazia di San Gerolamo al Monte di Portofino when news of Samanta’s indictment came to my notice. Heresy was common throughout Italy and the Holy Roman Empire in those days, and our Holy Father Pope Urban V was constantly raising armies and dispatching holy inquisitors to root out those who challenged the authority of the Church, but the crimes of witchcraft and sorcery were more unusual, and attracted my attention.

The local bishopric had adopted the chapter house of the Abbazia as its new seat, and seeing as the bishop was in residence during my stay, I petitioned that I might attend the trial as an expert, or even preside over it if a judge had not already been appointed. I was an inquisitor myself then, and enjoyed the unique dispensations and privileges that were afforded to that office, including participating in trials and litigations that fell outside my own region.

The bishop, Apollonio Fidelo, seeing no reason to object, granted me his blessing and gave me access to the Abbazia’s municipal library, where I spent a few days reviewing the literature and case history on heretical sorcery and witchcraft. I took charge of one of Fidelo’s novices, a sober young man called Marco di Verscaccio, who was learning his craft as a notary, and set him the task of collating the cases and information I deemed to be relevant.

Bussana was only a day’s travel north from the Abbazia, but Marco and I travelled a few days early to settle in and familiarise ourselves with the trial and its participants. The trial proceedings would take place in the chapter house of a small, rustic abbey dedicated to St Jerome a little way outside the village limits. The abbey was set into the higher ground that climbs away from the Legurian coast, surrounded by woodland and grapevines. The monks here—Benedictines, as were the monks at the Abbazia di San Gerolamo—welcomed me with some ceremony, and were pleased to have my expertise to support the trial.

After we observed Vespers at the lighting of the evening lamps, my assistant Marco retreated to the cell that had been readied for us, and the abbot, Father Riche, invited me to his solar, where he poured me a cup of the local wine. Riche explained his extreme nervousness about the charge of heretical sorcery.

‘Samanta is frightened,’ he said. ‘She has a mother and father of good standing and the family has been in this village for generations. She has never hurt anyone, and this accusation is very grave.’ ‘And who has denounced her?’

‘His name is Serge.’ Riche frowned, and he crossed himself. ‘A wanderer. He has been in Busanna for a matter of months but he is clever with his tongue, and knows how to manipulate people. Ever since the Black Death people have been frightened of the wrath of God, and are easily persuaded to find scapegoats for things they cannot explain. I suspect that this Serge is playing with people’s fears, but I do not understand why he would want to.’

‘The wrath of God rarely manifests itself on this earth,’ I said, ‘Whereas His love does so every day. The Black Death may have been an intervention by God, but we must also understand its mechanisms. In China, which was also riven by plague, a scholar named Tsao Yuan-Fung wrote of something called miasma theory, which states that such diseases are the result of the natural cycles and movements of the gases and dusts of the world. Whether he is correct or not, whatever caused the plague here in Europe must have done so under the limits of reality imposed by God, but also must be a natural phenomenon which we can learn to protect ourselves from. I suspect Serge’s complaint has some other explanation.’

‘Bless you, Brother Jacobus,’ said the abbot, taking my hand. ‘Those are wise words. I hope you are right. The community will be devastated if Samanta is found guilty. I shall give thanks to God for your efforts, in any case. You say you are an inquisitor? You are most unlike the other one.’

I raised my eyebrows. ‘The other one? I read that the trial is being overseen by the local jurist, a secular man with little knowledge of ecclesiastical law. That is why I offered my services.’

‘That would be Raffaelle Mavelo. Yes, he has nominal jurisdiction over the procedure, but we are a small parish, Brother Jacobus, and Raffaele has no knowledge of litigations relating to sorcery, so he requested assistance from the Palais in Avignon, and they sent a Dominican monk by the name of Nastagio di Balino to provide the necessary legal expertise.’

I sighed at the mention of that name, and muttered an oath under my breath. This did not go unnoticed. ‘You know him?’

‘I do. He and I have somewhat different methods. Brother Nastagio is certainly as godly in his intent as anyone you could meet, but almost sinful in his zeal for his work. He spent his early years flushing out the very last dregs of the wretched Waldensian heretics and burning them on pyres. He has recently been modifying and applying the work of the Spanish jurist Nicholas Eymeric to show that the practises of magic, alchemy, sorcery, and demonology are tantamount to heretical depravity, and must be prosecuted with the full authority of the Church.’

Riche crossed himself again in some agitation. ‘Heresy? Surely not again!’ ‘Again?’

‘At the end of the last century the followers of Fra Dolcino passed through Cuorgnè, a town not far from here, and they brought with them his penchant for challenging the authority of those such as myself, and his disdain for serfdom. The Dulcinians burned down a tithe belonging to Cuorgnè’s prebender, proclaiming its earthly belongings, pitiful though they were, to be a mark of great sin and a symbol of the corruption of the Church, which they were committed on purging. The Ancient Serpent still wends his way to the Garden! The inquisitors, filled with fury, overcompensated. They responded by burning not just the Dulcinians, but everyone who wouldn’t or couldn’t testify to their whereabouts.’ He looked at me very watchfully, all of a sudden on his guard. ‘And what

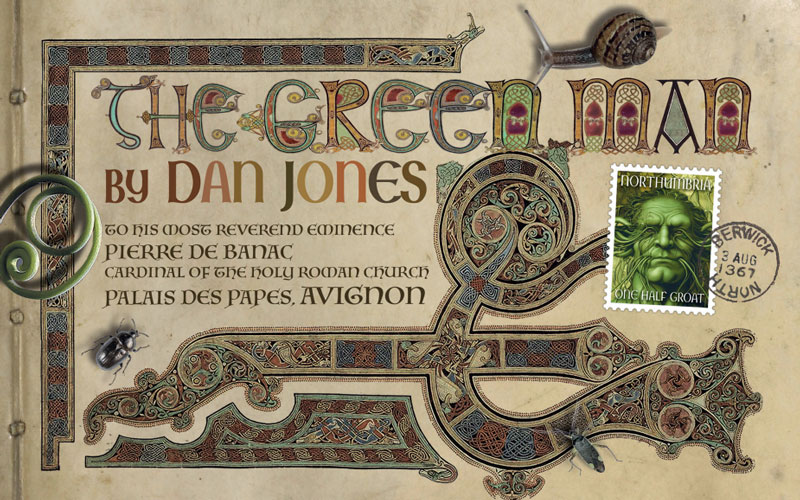

END OF SAMPLE THE GREEN MAN

DAN JONES

EnvelopeBooks, 24 April 2025 Softback, 400 pages 9781915023544 Advance copies and book club orders from envelopebooks.co.uk