America and Russia have entered into a pact that threatens to dominate the world by lying, bullying and intimidation. We’ve been here before

CTLASSIC FROM ENVELOPEBOOKS

The outbreak of war in September 1939 was almost a relief. It was like feeling ill and eventually finding out what is wrong with you: however bad the diagnosis, once you know what you’ve got, you can summon the strength to deal with it. At last we knew where we were: Germany had invaded Poland and Britain and France had declared war. It had happened.

Even before that, the Non-Aggression Pact signed between the Nazis and the Soviets in the summer of 1939 had disrupted the lives of my family. A condition of the Pact was that Northern Moldavia, which was then part of Romania, should be handed over to the Russians. They marched into Cernauţi without warning and my parents had to flee, abandoning their possessions. They took refuge with me in Bucharest.

This strange and sinister new alliance had plunged me even further into mental turmoil. Nothing made sense anymore. Authors I respected—André Gide for one—still praised the achievements of Soviet Russia. On the other hand, a charismatic tutor I had studied under at Bucharest Art School, who had been an ardent believer in Communism until the Moscow show trials, had completely lost his faith in it. I listened to him talk about the great delusion of his life and I had to admit to myself that the Communists, once they were in power, did not seem to have ushered in a reign of happiness and prosperity.

But I and people like me still pinned our hopes on the ideals of Socialism. We clung to the possibility that the system might evolve and we still had faith in Trotsky, the heroic exile who fought for revolution wherever he went; until, in 1940, Stalin sent a killer to Mexico to do him in.

I was in a living nightmare of confusion. I tried desperately to reason my way out of it, still in spite of everything hoping to discover a new morality in idealistic Socialism to counter the amorality of Fascism. I had some friends among the handful of committed Communists. There was a Surrealist painter called Perahim, who made no secret of his proletarian views and soon left for the Soviet Union, and a couple of journalists: Selmaru, who got by under the cover of editing a rightwing review, and Mihnea, who just kept quiet.

Then there was the musician Socor, who had caused a scandal by wearing a red jacket when conducting a concert. I had a lot of respect for his strength of character and painted his portrait at about this time. He had given up the red jacket but he took my breath away when he talked with all seriousness of the wicked Finns, who were a mortal threat to the Russian lamb and would have to be dealt with: this was Soviet politics at its most indefensible.

To tell the truth, I was never much good at following the herd or accepting other people’s belief systems. I just wanted to forget about politics and throw myself, heart and soul, into the joy of discovering my art. Every day I forced myself to shut everything else out of my mind and get on with my new picture, planning the composition, building up colour where I wanted it, but every time I started to make some headway, the brutal shock of communiqués from the war and the relentless flood of appalling events nearer home brought me to a standstill. The annihilation of the gallant Polish cavalry by gallant German tanks was horrifying but here in Bucharest we were even more shaken by the legionaries’ summary execution of the President of the Council for the crime of having declared his support for the Allies, and the subsequent massacre of his executioners by the police. Their bodies were laid out in the street for all to see.

In the summer of 1940, Antonescu and his fascist Iron Guard gave the German army permission to enter Romania (which they needed as a base for their eastern offensive). Bucharest was flooded with soldiers in green shirts armed with revolvers.

Ever yone was afraid, especially the Jews. Some of them managed to escape. Others bought their way out of trouble by handing over their property, little by little, if possible, spinning things out for as long as they could. They were subjected to ‘special treatment’, drafted to work (clearing snow in winter, for example) in incongruous units specially contrived for the amusement of their supervisors: students with old people, financiers with tramps, cripples with dancers. But more serious anti-Semitic measures were on the horizon. There was a monstrous feeling of unease.

In all this I had a sense that I was destined to play some part. I had a dream in which, on the point of death and supported by my mother, I touched the hands of the sick and mutilated and they miraculously became whole again—a dream echoed one day in real life. I was walking along one of the main streets in Bucharest and came upon a group of peasants who drew apart as I approached, so that I found myself encircled by them. A big grey dog was in the middle of the space, his eyes fixed on me. I went up to him and patted his head. No one said anything. It was sunny, the sky was blue, and they all stared at us in silence. Uncomfortable with this attention, I moved away and, as they drew back for me to pass, I heard a few mutterings: ‘We thought you’d come to deal with him. We’ve informed the authorities that there’s a mad dog in the street … .’ I looked back towards the dog: his eyes seemed to be fixed on me and he was slavering.

It was during this time, after the fall of France, that I began to be more aware of the British and their heroic stand against the forces of darkness. We were already learning to be careful about revealing ourselves to other people, including even our neighbours, and every evening, alone with my family, we gathered round the radio to listen to the BBC calling out to all people horrified by the menace of the fascist and Communist dictatorships—everyone who refused to accept defeat. The BBC’s never-failing news broadcasts beamed through the fog of falsehood and deception. The words of Churchill, the declarations of De Gaulle, the ringing music of the Marseillaise, shone like white stones marking a road through the night.

France is not dead! France is no longer completely in the power of the little Hitlers now marching under the Arc de Triomphe!

Then softly, over music:

Radio Paris tells lies! Radio Paris is lying! Radio Paris is German!’

And the warning,

Be careful! Turn down the volume if you think anyone might hear you!

Some time during that autumn of 1940 I rented a gallery. I was planning to put on an exhibition the following January and, with my parents still staying with me, I needed more space to get it ready. This gave me just about enough time to prepare the frames, which I had designed myself, adding

END OF SAMPLE

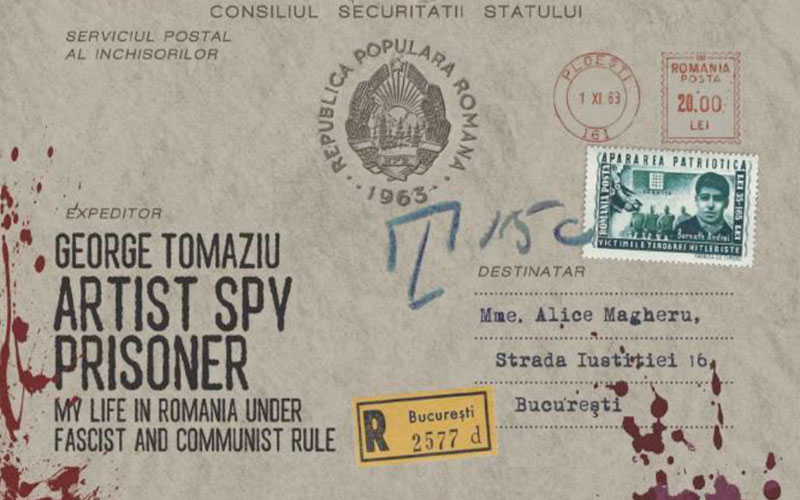

ARTIST SPY PRISONER

GEORGE TOMAZIU

EnvelopeBooks, 3 April 2025 Softback, 228 pages 9781915023063

Advance copies and book club orders from envelopebooks.co.uk