When you’ve spent much of your career as a senior exec in the tobacco business, you’re bound to see the world, and your place in it, differently. But what can you teach us?

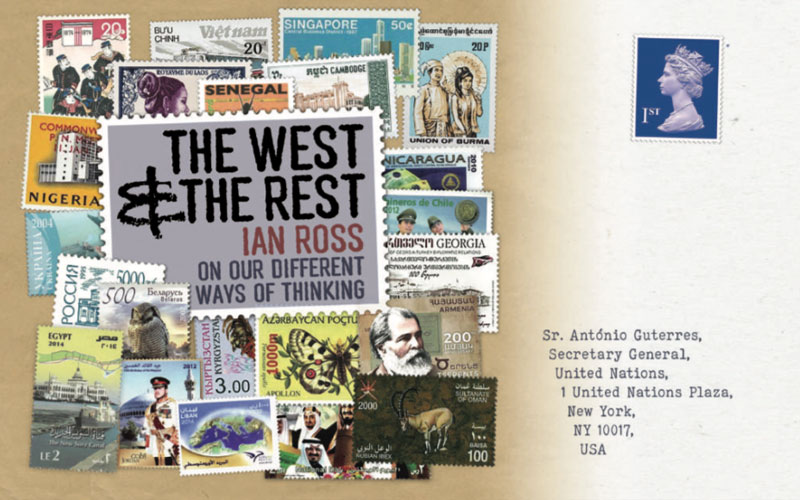

NEW FROM ENVELOPEBOOKS

Leaving Laos for the first time was like walking out of a cinema halfway through the feature. I was an expert on one nation in South-East Asia, or so I thought, and assumed that everywhere else in that region was more or less the same. Then my work with BAT took me elsewhere—to Latin America, Finland and New Zealand—before a posting to Singapore in 1998 gave me the chance to fill in the gaps.

It was the Vietnam War (or, more correctly, the Second Indochina War) that provoked the first collective sense of moral conscience about events far from home for Western baby boomers (of which I am one). That awakening has in no small way influenced attitudes towards the rest of the world. What it lacks, however, is nuance.

Vietnam, viewed from afar, became a land of myths. It was the first war that became public property: the photos of the monk immolating himself; the naked girl-child running from a napalm raid; the Vietcong officer being executed in the street by a bullet to the temple, capturing that instant between life and death; and finally the last helicopter on the American Embassy roof, above a rickety ladder, with hundreds of terrified people below, scrabbling for the last remaining seats.

How the mighty had fallen. It was a land of terror and trauma, and those exposed to it constructed their own stories as well as they could to make sense of what they had experienced. On 30 April 1975, nearly thirty years after Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of Vietnamese independence in 1946, it was all over. Nearly thirty years: an entire generation.

Graham Greene’s The Quiet American had influenced my teenage impressions of what Vietnam was like. This was a place of moral ambiguity where a man could live as he liked but remain in danger. Experience taught you how to survive but made you more cynical and callous in the process. I liked this idea of being tested, to find out what moral backbone I had, if any. And I could almost smell it—the humidity and the heat and the sight of black-clad figures emerging from the tree line with AK-47s blazing.

I had got close to this in Laos, but too late to witness it. Returning home, I discovered that my well-educated friends were not interested in my stories. The people had won and America had lost and that was that. The world

is a complicated place and the temptation to pigeonhole anything from afar as good or bad is often convenient but lazy. Vietnam had become a hermetically sealed, hard-line Communist state.

But I still wanted to go there, an interest piqued not by retracing the Second Indochina War’s road to ruin (though it remained a preoccupation of those who had lived through it) but by what happened once the Stars and Stripes were lowered for the last time, folded for the last time and placed in the helicopter that departed Saigon for the last time.

The announcement in 1986 of a new policy of Do Moi, an opening up of Vietnam’s doors to the outside world, provided commercial opportunities that would foster a socialist-oriented market economy. By then I was in Singapore, and married with three small children. Since the fall of Saigon little had been heard of Vietnam, save the invasion of Cambodia to overthrow the Pol Pot régime, and the refugee crisis of the boat people who risked their lives in barely seaworthy fishing boats to get out of the country. That event, which captured the world’s headlines for a few weeks, now seems forgotten. Two million ‘disappeared’, never to be reported on again, to make the best of their new lives overseas and became collectively anonymous.

The one pro-Western country with flights to Ho Chi Minh City was Thailand but there were just two flights a week and entry visas were only obtainable in Bangkok. The embassy proved to be an unkempt little bungalow, almost invisible, tucked away down a soi off Sukhamvit. Surprisingly, it proved efficient. I and my most adventurous colleague Wang Tee Fock, the production director, were expected, and our visas would be ready the following morning.

We flew to Ho Chi Minh’s Tan Son Nhut airport on Friday, 23 September 1988, arriving at dusk, having flown over the Mekong Delta, which seemed to be three-quarters water, in paddy fields, rivers, canals or bomb craters. Photography was forbidden both in the air and on the ground. The plane was parked in a corner of the airfield next to an abandoned control tower and we waited in light rain for the ancient DeSoto school bus to take us to the terminal. An equally ancient articulated fuel truck rumbled past, none of its lights working but the faded Shell logo still discernible.

The terminal was the second indication of a time warp. It seemed to be imperceptibly dissolving into its own foundations. This seemed of no consequence to the officials, who performed the formalities efficiently. Outside, far too many people were awaiting the few passengers. We were met by the Vietnamese delegation and loaded into a newly imported Japanese microbus. The only other four wheeled vehicles were remnants from pre-revolutionary days.

Our destination was the Rex Hotel. This had been reserved for US officers during the war, and in consequence had its bar on the roof, beyond the reach of hand grenades. My room was a time warp; it looked as if nothing had been touched since 1975, with a colour scheme—dark brown highlighted by orange—redolent of that bygone era. A functioning Carrier box air-conditioner was fitted into the window frame. The bathroom was swathed in blue micro-tiles and the fittings were universally American: stained but functioning. I was half-convinced that I was being monitored and I looked for signs of concealed microphones, but found nothing. The following morning I took care to leave a hair in the lock of my suitcase to see, when I got back, if it had been disturbed while I was out. Despite the dilapidated state of everything, I still believed that this authoritarian state took a close interest in the activities of all foreigners, and we were few and far between at that time.

My room felt initially like a prison,

END OF SAMPLE

THE WEST AND THE REST

IAN ROSS

EnvelopeBooks, 3 April 2025 Softback, 384 pages 9781915023537

Advance copies and book club orders from envelopebooks.co.uk