A second-generation Irishman on the subject of ‘cultural appropriation’

BOOK DATA

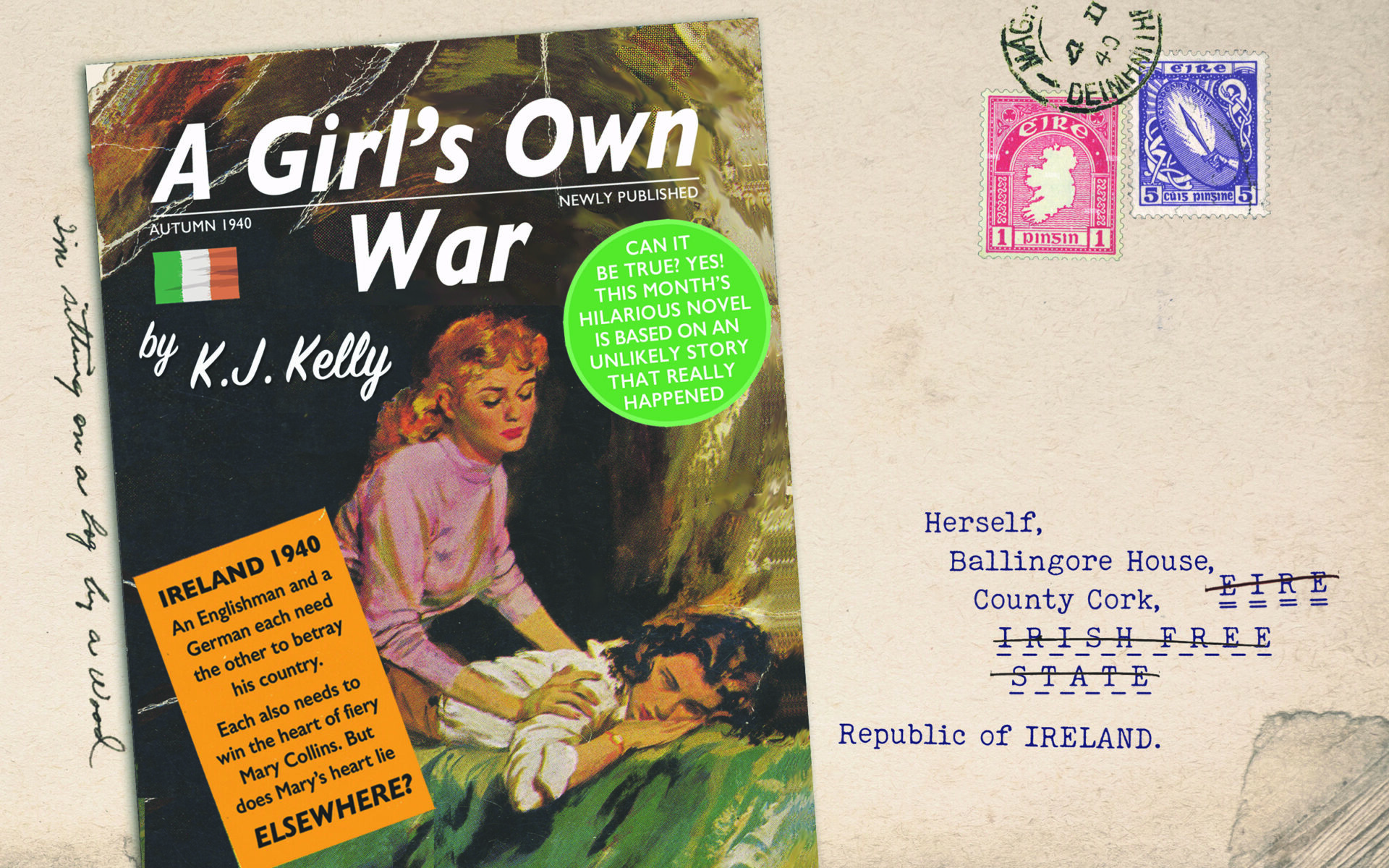

A GIRL’S OWN WAR

K.J. KELLY

EnvelopeBooks

7 September 2023

Softback, 246 pages

9781915023148

RRP £12.95

No one finds it odder than I do that my first novel, A Girls’ Own War, turned out to be a comedy. It is, after all, set in a deeply troubled time and place and is being read in equally troubling circumstances. Who in their right mind finds conflict, poverty and desperation funny?

The novel certainly didn’t start out that way. I have family connections with County Cork, and with good people who put me up during my school holidays and put up with my mischief-making, without ever mentioning a word to my parents. I ran as wild then as I do in my imagination now—and that’s the problem, because my story of a small coastal town near the very southern tip of Ireland in 1940, overwhelmed my usual means of story-telling. And not for a minute would I want to patronise them.

It’s a truism that fact is stranger than fiction. One of my characters in wartime neutral Eire is John Betjeman, who would go on to become Britain’s poet laureate. I could not—or would not—have invented his presence there; I have no wish to create false history. But there he trod, or bicycled, writing to his Irish muse, Emily, commiserating with her being stranded with a “stone-age” people.

There were other equally unlikely but entirely historical characters who washed up on the spit of land that is Ballingore, West Cork. In passing, these included Royal Naval Flight Arm officers who crashlanded and were interned on Ireland’s non-combatant soil, as well as sundry German submariners and the blackmailing brother of Brendan Bracken, Churchill’s parliamentary private secretary.

As with Prospero’s island, what brought them there—a spell-induced storm or the dogs of war—is mere device. But for a while, a year after the war with Hitler had begun, Ballingore was a dramatic spot, for Britain and for Germany, both deeply involved in the Battle of the Atlantic, and for the people who lived there.

Among them was my father, the wee’st of wee boys in 1940. If asked, I’d say the inspiration for A Girl’s Own War was the photo of him, in blackface, with a dish of exotic fruit on his turbaned head. He is seen attending upon a group of mousta chioed young men, in “Arabic drapes”, performing a pantomime at Ballingore House, the estate of the Anglo-Irish Lord White, who gave bed, board and booze to any Allied airman who unwittingly set foot on Eire’s holy neutral turf. They merely had to sign the guestbook and promise not to escape.

My Dad had nowhere to escape to.

Was he traumatised by the experience? He didn’t ever say so—he wasn’t that sort of father—and I didn’t delve. Besides, what really captured my interest was the dark-eyed young woman, almost out of shot. My old man remembered her, vividly. “That one,” he said, “ran with the hare and mixed with the pack, for she loved the chase.” Her name was Mary, he said, and she could be posh and she could be of the plain folk, just as it suited.

But always she was ambitious. How those fly boys danced on her attentions.

My attention was piqued, because when I hear the experiences of my parents’ generation, of their childhood in the 40s and 50s in Ireland, there is one constant and compelling refrain: how they negotiated class.

My folks were from a fragile position in a country that had only recently achieved independence. They were from what used to be known as the petit bourgeois. My grandfather was the master stonemason for Lord White’s estate, which is how my father came to be available for small dramatic parts. And my mother’s people kept shop, providing tea, bacon and mustard on tick to the lower gentry—lower, at least, than Lord White, who was more usually provisioned by Fortnum and Mason, depending upon what the sailing conditions were like.

As for the poor of the town, they had to pay on the nail. That always fascinated me: ‘thems that can don’t have to, thems that can’t can go hang’.

Apparently the bills run up by the landowning types turned my granny’s hair grey at thirty. If she quibbled—read, “begged”—they would reply that dumb insurrection by ignorant Fenians had caused the hard-ship in the first place, provoking “mainland Britain” into its economic blockade of this, John Bull’s other island. The underclass had chosen to unmake the bed, now they must lie in it.

From my boyhood holidays I recall their reminiscences of how dire the 30s were in Southern Ireland, or Eire, or whatever name it had taken since it had thrown off the yoke of the crown. No meat or cheese was allowed east across the Irish Sea, and poverty hardened—ossified. One had to cleave to the landed class because they alone might offer some work, or even one day settle their bills.

The result was that a class of poor was rendered more docile than it had been under British rule. Indeed, it became obvi ous that Eire was independent in name only. The old land-holding governing class could not be ousted but had to be clung to, as a yachtsman must cling to an upturned boat, when miles from shore and in sore need of help.

But then came the Emergency of 1939, the decision to remain neutral, and the demands for food and sustenance from wartime Britain. Up went the prices of beef and butter and money at last began to flow through the veins of the economy and into the pockets of drapers and publicans. On the Atlantic-facing West Coast there was the excitement of the battle of the boats—those of the Allied type that flew and those of the German type that could submerge. Inevitably, men and machines washed ashore.

What was the cap-doffing stonecutter or the curtseying shopkeeper to do? Keep their bets open, loyalty-wise; that’s how I heard it, across the pitch-pine table. Why, it could be swastikas in the town square by teatime, or the Brits might just as readily take back the port they had kept, post-independence, until 1937. It’s a juicy bone to thicken any plot, but my loyalties came to lie elsewhere.

Besides, I knew my parents’ story, as much as any offspring can. They were still alive and I hate hurting anyone’s feelings, even for money. The truth was that by the time I reached my early-middle years, I was smitten by the dark-eyed one—her in the photo: Mary. In her face I saw excitement, intense curiosity and that slight furrowing about the temples that tells me she’s sizing up an opportunity.

And why not? Ballingore was as noisy and bright as a musical in the autumn of 1940—at least in comparison to the pre-war years.

So A Girl’s Own War is the story of the trials and machinations of Mary—let’s call her Collins. Plain Mary Collins. (She’ll have to explain the absence of a middle name for I know how much a saint’s or a patriot’s moniker prefixing a surname is prized in Ballingore.) She’ll be peeved for sure. How to express peevishness? Ah, she’s a convent-educated young woman, of impeccable Catholic tastes and habits, landless but marriageable, desperately seeking sanctuary and sanctity. Poor Mary: a patriot, obviously, but immune to the romance of the revolutionary pitch fork. And at nineteen, not entirely grown out of schoolyard smut. She’s pious, then, and profane.

How does Mary tell her story? To whom? To me? Heaven forbid, how unsavoury. No, she has a friend—or, rather, she’s made to take a friend, one who is a true child of the very plain people and who cannot help but speak truth to power, who everyone agrees will keep Mary on the straight and narrow but secretly has more ambition than Mary possesses in her middle finger.

She’s smart too, this Niamh Slattery. Imagine having to thread your way through the chicane of small-town gossip and the slick overtures of the Brylcreemed squad, not to mention the sickly doggerel of the English poet. Why, these girls are for the taking, no? Or, at least, for the taking down a peg or two, say the townspeople.

Yes, yes, I invented Naimh to save Mary. It’s my love story too. But I try not to intrude; I let them talk their troubles out in rhyme and riddle. They don’t use standard Irish, or even, Oirish. That’s not what I’m hearing, for these two are wiseacres, throwing out lines to entertain each other. Don’t all close teenage pals have their own language?

Perhaps it is unseemly to listen in but honestly, I can’t help myself. Mary and Niamh made me write it down so I wouldn’t forget, so I might read their lines back and cheer them on for their pluck, lack of luck and sheer perseverance. Yes, they are oblivious to the great affairs of state and family, but that is the point of being nineteen, wide-eyed and rather cunning. I have no wish to go back but I still want to remember how it was.